Friends,

Do you recall a time when the income of a single schoolteacher or baker or salesman or mechanic was enough to buy a home, have two cars, and raise a family? I do.

In the 1950s, my father, Ed Reich, had a shop on the main street, from which he sold women’s clothing to the wives of factory workers. He earned enough for the rest of us to live comfortably. We weren’t rich but never felt poor, and our standard of living rose steadily through the 1950s and 1960s.

That used to be the norm. For three decades after World War II, America created the largest middle class the world had ever seen. During those years the earnings of the typical American worker doubled, just as the size of the American economy doubled. Over the last thirty years, by contrast, the size of the economy doubled again but the earnings of the typical American went nowhere.

Then, the CEOs of large corporations earned an average of about twenty times the pay of their typical worker. Now they get substantially over two hundred times. In those years, the richest 1 percent of Americans took home nine to ten percent of total income; today the top 1 percent gets more than twenty percent.

Then, the economy generated hope. Hard work paid off, education was the means toward upward mobility, those who contributed most reaped the largest rewards, economic growth created more and better jobs, the living standards of most people improved through their working lives, our children would enjoy better lives than we had, and the rules of the game were basically fair.

But today all these assumptions ring hollow. Confidence in the economic system has sharply declined. The apparent arbitrariness and unfairness of the economy have undermined the public’s faith in its basic tenets. Cynicism abounds. To many, the economic and political system seems rigged.

THE THREAT TO CAPITALISM is no longer communism or fascism but a steady undermining of the trust modern societies need for growth and stability. When most people stop believing they and their children have a fair chance to make it, the tacit social contract societies rely on for voluntary cooperation begins to unravel. In its place comes subversion, small and large – petty theft, cheating, fraud, kickbacks, corruption. Economic resources gradually shift from production to protection.

The nation becomes susceptible to demagogues such as Donald Trump.

We have the power to change all this, recreating an economy that works for the many rather than the few. But to determine what must be changed, and to accomplish it, we must first understand what has happened and why.

For a quarter century, I’ve offered in books and lectures an explanation for why average working people in advanced nations like the United States have failed to gain ground and are under increasing economic stress: Put simply, globalization and technological change have made most of us less competitive. The tasks we used to do can now be done more cheaply by lower-paid workers abroad or by computer-driven machines.

My solution has been an activist government that raises taxes on the wealthy, invests the proceeds in excellent schools and other means people need to get ahead, and redistributes to the needy. These recommendations have been vigorously opposed by those who believe the economy will function better for everyone if government is smaller and if taxes and redistributions are curtailed.

WHILE THE STANDARD EXPLANATION for what has happened is still relevant, it overlooks a critically important phenomenon: the increasing concentration of political power in a corporate and financial elite that has been able to influence the rules by which the economy runs.

And the governmental solutions I have propounded, while I think still useful, are in some ways beside the point because they take insufficient account of the government’s more basic role in setting the rules of the economic game.

Worse yet, the ensuing debate over the merits of the “free market” versus an activist government has diverted attention from several critical issues: how the market has come to be organized differently from the way it was a half-century ago, why its current organization is failing to deliver the widely shared prosperity it delivered then, and what the basic rules of the market should be.

The diversion of attention away from these issues is not entirely accidental. Many of the most vocal proponents of the “free market” -- including executives of large corporations and their ubiquitous lawyers and lobbyists, denizens of Wall Street and their political lackeys, and numerous multi-millionaires and billionaires -- have for many years been actively reorganizing the market for their own benefit, and would prefer these issues not be examined.

MARKETS DEPEND for their very existence on rules governing property (what can be owned), monopoly (what degree of market power is permissible), contracts (what can be exchanged and under what terms), bankruptcy (what happens when purchasers can’t pay up), and how all of this is enforced.

Such rules do not exist in nature. They must be decided upon, one way or another, by human beings. These rules have been altered over the past few decades as large corporations, Wall Street, and wealthy individuals have gained increasing influence over the political institutions responsible for them.

Simultaneously, centers of countervailing power that between the nineteen-thirties and nineteen-eighties enabled America’s middle and lower-middle classes to exert their own influence -- labor unions, small businesses, small investors, and political parties anchored at the local and state levels -- have withered.

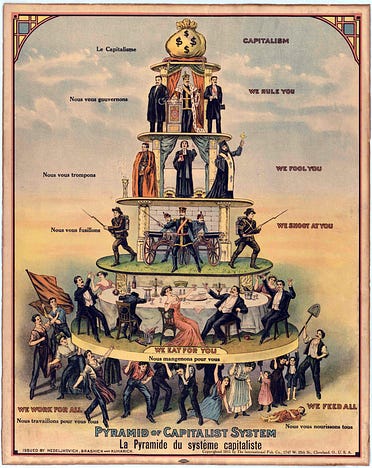

The consequence has been a market organized by those with great wealth for the purpose of further enhancing their wealth. This has resulted in ever-larger upward distributions inside the market, from the middle class and poor to a minority at the top. Because these distributions occur inside the market, they have largely escaped notice.

The meritocratic claim that people are paid what they are worth in the market is a tautology that begs the questions of how the market is organized and whether that organization is morally and economically defensible. In truth, income and wealth increasingly depend on who has the power to set the rules of the game.

CEOs of large corporations and Wall Street’s top traders and portfolio managers effectively set their own pay, advancing market rules that enlarge corporate profits while also using inside information to boost their fortunes.

Meanwhile, the pay of average workers has gone nowhere because they have lost countervailing economic power and political influence. The simultaneous rise of both the working poor and non-working rich offer further evidence that earnings no longer correlate with effort.

All of this has brought us Donald Trump and America’s lurch toward fascism.

The solution is not less government. The problem is not the size of government but whom the government is for. The remedy is for the vast majority to regain influence over how the market is organized. This will require a new countervailing power, allying the economic interests of the majority who have not shared the economy’s gains. The current left-right battle pitting the “free market” against government is needlessly and perversely preventing such an alliance from forming.

The biggest political divide in America in years to come will be between the complex of large corporations, Wall Street banks, and the very rich that has fixed the economic and political game to their liking, and the vast majority who, as a result, have found themselves to be in a fix.

The answer is not to give up on democracy.

To the contrary, the only way to reverse course is for the vast majority who now lack influence over the rules of the game to become organized and unified, in order to reestablish the countervailing power that was the key to widespread prosperity five decades ago.

While I focus on the United States, the center of global capitalism, the phenomena I describe are increasingly common to capitalism as practiced elsewhere around the world, and I believe the lessons drawn from what has occurred here are as relevant to other nations.

Although global businesses are required to play by the rules of the countries they do business in, the largest global corporations and financial institutions are exerting growing influence over the make-up of those rules wherever devised. And the cumulative frustrations of average people who feel helpless and powerless in the face of economies (and market rules) that are not working for them are generating virulent nationalist movements, sometimes harboring racist and anti-immigrant sentiments, as well as political instability in even advanced nations around the globe.

IF WE DISPENSE with mythologies that have distracted us from the reality we find ourselves in, we can make the system work for most of us — rather than for only a relative handful.

History provides some direction as well as some comfort, especially in America, which has periodically readapted the rules of the political economy to create a more inclusive society while restraining the political power of wealthy minorities at the top.

In the 1830s, the Jacksonians targeted the special privileges of elites so the market system would better serve ordinary citizens. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, progressives enacted antitrust laws to break up the giant trusts, created independent commissions to regulate monopolies, and banned corporate political contributions. In the 1930s, New Dealers limited the political power of large corporations and Wall Street while enlarging the countervailing power of labor unions, small businesses, and small investors.

The challenge is not just economic but political. The two realms — economics and politics — cannot be separated. Indeed, the field on which I draw used to be called “political economy” -- the study of how a society’s laws and political institutions relate to a set of moral ideals, of which a fair distribution of income and wealth was a central topic.

The emergence of economics as a discipline distinct from political economy began in 1890 with the publication of Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics. The new discipline sought to identify abstract variables applicable to all systems of production and exchange, and paid little or no attention to the distribution of those resources or to a specific society’s legal and political institutions.

The study both of economics and of many other aspects of society thereafter began shifting from historically-specific political, moral, and institutional relationships to more universal and scientific “laws.” John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) dominated American economic policy from the end of World War II until the late 1970s.

After World War II, under the powerful influence of Keynesian economics, the focus shifted away from questions of politics and morals and toward government taxes and transfers as means of both stabilizing the business cycle and helping the poor. For many decades this formula worked.

Rapid economic growth generated widespread prosperity, which in turn created a buoyant middle class. Countervailing power fulfilled its mission. We did not have to attend to the organization of the political economy or be concerned about excessive economic and political power at its highest rungs. Now, we do.

In a sense, then, these essays harkens back to an earlier tradition of inquiry, and a longer-lived concern. My optimism is founded precisely in that history. Time and again we have saved capitalism from its own excesses. I am confident we will do so again.

***

I urge you to add your comments, take part in our discussion, and share with others.

Thank you for joining me on this expedition.

Subscribers to this newsletter are keeping it going. If you are able, please consider a paid or gift subscription. And we always appreciate your sharing our content with others and leaving your thoughts in the comments.